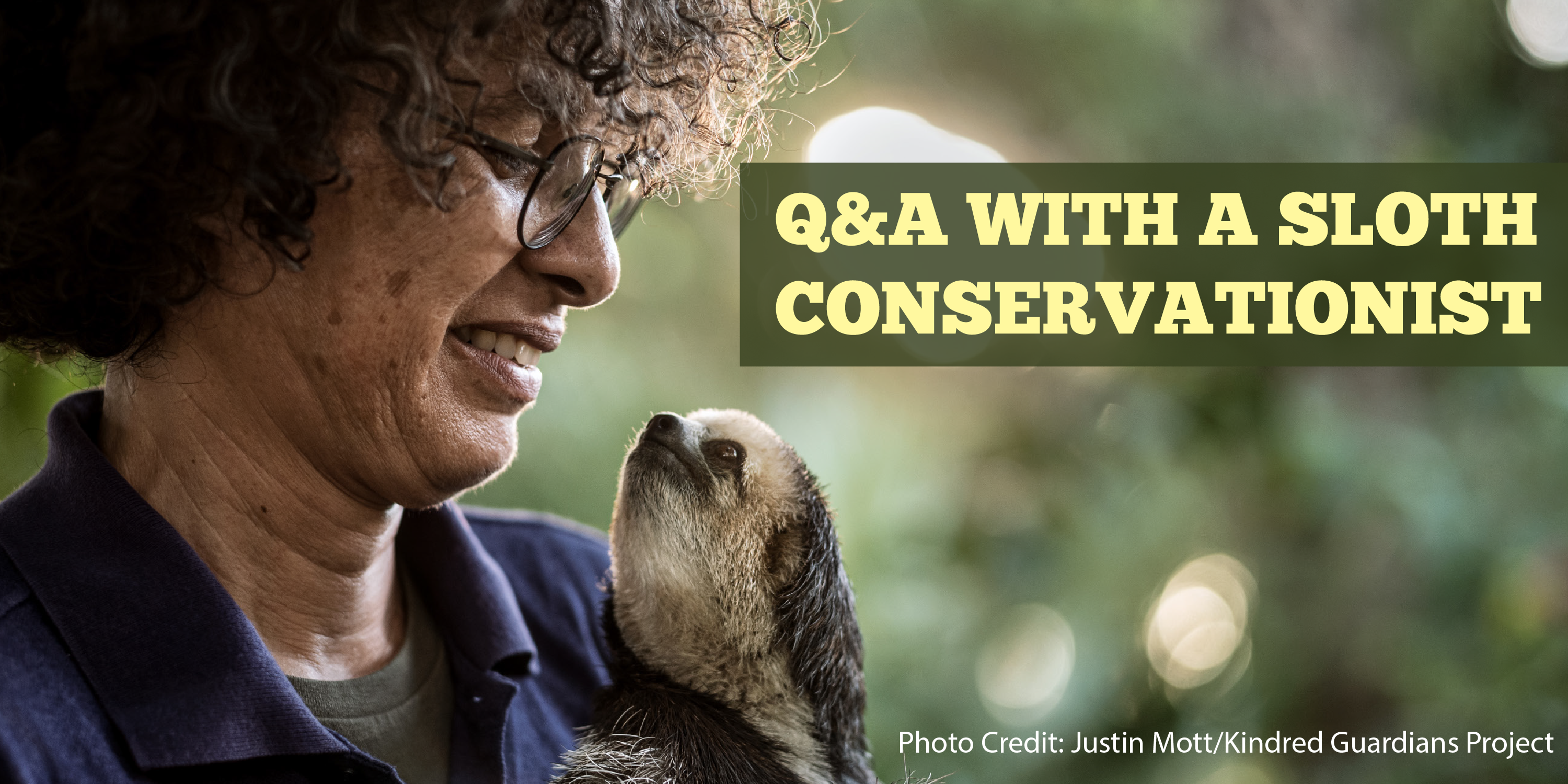

Monique Pool is the founder of Green Heritage Fund Suriname. The foundation’s mission is to move all Surinamers to make wise decisions for the sustainable use of natural resources. This month, Monique will share her work with sloths in presentation on our Facebook and YouTube Live. She was kind enough to answer some questions for us in advance.

What inspired you to found the Green Heritage Fund of Suriname?

In 2005 my dog went missing after some people living behind me who were celebrating a wedding, lighted some firecrackers. My dog ran away and, when I went looking for her, I came in contact with the animal shelter where they had received, on top of all their other daily challenges, a baby three-fingered sloth. As a volunteer for the Animal Protection Society of Suriname I took the animal in to care for it. Then I started taking all calls that had to do with anteaters, sloths and armadillos. In particular sloths were facing a lot of problems in the urbanized area. That’s when I decided to set up a foundation, so that any money raised using the image of the sloths I was rescuing would be used to improve their fate.

What surprised you the most when first working with sloths?

First thing I have to mention here: in Suriname we have two species of sloths that are very different from each other. The pale-throated three-fingered sloth (Bradypus tridactylus) and the southern two-fingered sloth (Choloepus didactylus), mind you, in your searches you will find that people write and speak about three-toed and two-toed sloths, however, all species have three-toes, so we decided to distinguish them based on their fingers. Because it caused confusion when we went on rescues. To come back to your question: what surprised me most was how intelligent they are! They are portrayed in so many books, articles, and online as slow and dumb. That’s absolutely not true. They are very intelligent. They teach each other things. For example, when I was still running the shelter out of my house, they had taught each other how to open the door of the bathroom in which they spent most of their time. They also have an incredible spatial memory, once they have used a certain path to go somewhere, they can always find it back. And they are very clean. They spent around two hours each day combing their fur, and they do that in a very systematic manner. So when people who want to keep them as pets (which is illegal in my country), cut off their claws, it not only provides a problem because they can no longer climb effectively, but they can also no longer keep their fur clean, leading to outbreaks of parasites in their fur.

Green Heritage Fund Suriname is in Paramaribo, Suriname, South America. What are the main threats to sloths in Suriname?

Habitat loss due to urbanization, human infrastructure and humans and their pets. They are confronted with habitat loss in the areas they most occur in. The areas where there is maximum entropy. That means where all circumstances for their survival are most favorable. The most urgent thing we need to find a solution for now are the effects of climate change on these species, especially drought.

“You do not need money to make positive steps for the environment.”

How do you know when a sloth is ready to be released back into their natural habitat?

Sloths are solitary animals and if they are adults and just in trouble for “trespassing” in someone’s yard or house, they can just be translocated to an area that is similar to where they come from and safer. So they are a very self-sufficient species. As long as you take them to an area with similar vegetation, they will be able to survive. This is true for both species.

Photo Credit: Justin Mott/Kindred Guardians Project

You also act as Suriname’s Country Coordinator for the Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment (GLOBE) Program. How did you start your work with the GLOBE Program?

Since 2006 I became involved in dolphin monitoring in the Suriname River which flows out into the ocean and it is the river that our Capital, Paramaribo, is located on. As we developed a protocol to monitor this population of Guiana dolphins (Sotalia guianensis) one of the things we did was check the salinity, pH, temperature, and other parameters of the water these animals were swimming in. The former country coordinator heard about our work and he asked if I wanted to become the new country coordinator, as I was already doing hydrology measurements anyway. So then I read up on the program and I became really invested in it with our foundation. I think it is now time for a new country coordinator, and we do have some really good candidates, teachers and also some of my colleagues who are now even working on adding to the existing protocols. For example, we are working on adding a mangrove protocol, which will be a bundle of protocols that already exist and some new ones. For me GLOBE is the ideal way to get young people interested in the environment and science education.

What advice would you give someone who is interested in getting involved with conservation efforts?

My most important advice is you do not need money to make positive steps for the environment. Anyone can become involved in conservation, if now only from your home, start sharing posts from conservation organizations. If you want to be more invested, learn how to document what you see, study your species and ecosystem. And be a voice for those that cannot speak up for themselves, and that holds for single species, to whole ecosystems and goes for animals as well as plants. In the end we are all connected to each other and our planet through this web of life, of which we are still only scratching the surface. If you feel rather that you want to support the work of someone who is already involved in conservation, you can maybe volunteer and of course donations can also be made. However, a donation is great! We love donations, but it should not be just instead of doing something yourself as well.